Whenever I think of David Cronenberg, I think of the apostle Paul's diatribes against the flesh. He would have hated Cronenberg, whose films not only revel in flesh but insist on its liberating nature through terrifying mutations. They give fleshy form to insane ideas. They obsess pandemic outbreaks, failed scientific experiments, and cold clinical environments. The results are destructive, but also celebratory. And, of course, outrageously disgusting. But Cronenberg isn't just about shock value; there's always subtext and philosophy at work; he has a unique recipe for making art out of puke and gore. If in the last decade he's moved away from this venereal horror, he remains focused on mind-body relationships, now channeled through more realistic examinations of cyclical violence and sex. Here is his best work, ranked per the favorite director's blogathon. Happy New Year!

1. Videodrome. 1983. 5 stars. If there was ever a film that merits the cliche "like nothing you've seen before", this is it. The idea that watching videos can somehow physically change and corrupt you is quintessential Cronenberg, and involves everything from torture porn to sadomasochism to mind control, all weaved through the body horrors of flesh guns, male "vagina" slots that play VHS tapes, and cruel metamorphosis. James Woods fits perfectly in this stew as the CEO of a cable station who gets involved with conspiracies behind a snuff-film franchise, and becomes a pawn in a plot to broadcast its signal to millions of viewers. The mission is to create a "new flesh" by merging human consciousness with a media stream of sexualized violence, and the hyper-commentary is obvious: we're becoming dangerously complacent the more we evolve into a mass-media culture. By far Cronenberg's most original, intelligent, and disturbing film; and his ultimate masterpiece.

2. Crash. 1996. 5 stars. Cronenberg's most fucked up film -- and I mean that in a good way -- is a bit like Pink Floyd's The Wall: just watching it is a drug trip. It explores esoteric fetishism, in this case people who are sexually aroused by car crashes, even fatal ones, and study and ritually reenact the car accidents of celebrities. I would probably call Crash the most artistic NC-17 film I've ever seen. For all the racy material, it doesn't come across as sensational, in fact, just the opposite: it's incredibly subdued and polished. The cold blue look works wonders in this regard, and dialogue seems to be spoken through a dream-like filter. The parallel of surrendering to an automobile wreck and giving oneself up to a sex partner sounds too crazy to take seriously, but it works in context, and indeed this is one of Cronenberg's most serious films. According to him, Crash would have been a cheap Basic Instinct type of thriller in the hands of Hollywood; in his it approaches the artistic nihilism of Ingmar Bergman.

3. The Brood. 1979. 4 ½ stars. This angry film testifies to the nasty divorce Cronenberg was going through at the time, and also to the crank psychoanalytic movement of the '70s. Here the therapy is "psychoplasmics", which attempts to heal mental derangement by a gross physical change to the patient's body; the patient in question is a woman who was abused as a child, and is now in legal battle for custody of her five-year old daughter. In rage she gives birth to deformed children who go on killing rampages, and they even go after her daughter. What keeps this a stand out film is the level of child endangerment we rarely see anymore. The Brood is in some ways an indictment of irrational feminine power, and also contends with the other '79 body-horror classic Alien: the scene with Samantha ripping open her external sac and licking clean her mutant newborn is almost as horrifying as Kane's chestburster. I revere this film, it has high rewatch value, and I wonder if it would have been as effective if not for the personal rage Cronenberg was able to pour into it.

4. The Fly. 1986. 4 ½ stars. A doomed romance is as much responsible for this one's popularity as the hideous horror show. It's astonishing, actually, how much emotion The Fly packs, given the minimal development of Brundle and Veronica's love affair. As for the repulsion on display, it's shocking even for Cronenberg -- animals torn inside out, food being puked on for edible purposes, a woman's nightmare of giving birth to a huge obscene larva. So many scenes have taken on classic status, not least the tragic dialogue at the end, "I'm an insect who dreamed he was a man; but now the dream is over, and the insect is awake," followed by Veronica's anguish as she can barely bring herself to kill Brundle in an act of mercy. If there's any criticism I have, it's the omission of exceptionally gross scenes that were censored in order to keep our sympathy for the protagonist, which was completely unnecessary. Then there's the tacky '80s feel. But it's only little things that keep The Fly from a perfect 5-rating.

5. Eastern Promises. 2007. 4 ½ stars. When Cronenberg left the body-horror genre, reactions were mixed, but this film vindicates the move if nothing else. Viggo Mortenson reprises his shady figure from A History of Violence, but with far more realism and depth -- the fight scene in the bathhouse where he gets the shit kicked out of him is classic, and contrasts in every way with his superhero vanquishing of the thugs at the end of History. Indeed, Eastern Promises exudes a black discipline in every frame; it's Cronenberg's Godfather, no less, with London Russians instead of American Italians, but the same mafia codes of honor and shame, weaved around a business of sex trafficking and a mysterious baby whose mother was murdered. There is the striking absence of guns in favor of knives, which throws a more intimate spotlight on the question of brutal violence. It's as if Cronenberg wanted to show what he could really do this time with Viggo Mortenson as a paradox of corruption and justice, and the result is one of his most artistic films.

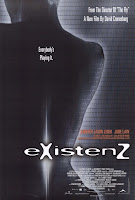

6. eXistenZ. 1999. 4 stars. Or The Matrix goes organic. Some believe this film perfected what Videodrome tried in the '80s, but they're in the minority, and I'm certainly not with them. It may be a cleaner and more logical look at virtual reality but doesn't come close to topping Videodrome's raw demented power, let alone innovation. That being said, I really like eXistenZ. It exploits multiple layers of stories within stories, with people assuming different but roles on each level (shades of the later Inception), so even by the end you can't be sure of what's really going on. There's also some fun philosophy about free will. The most notorious scene has Jude Law greedily devouring a disgusting "Chinese special" at a restaurant (it has to be seen to fully appreciate the greenish-black mess of amphibian pus and slime), while also grimacing like he wants to throw up. When his partner tells him he won't be able to stop himself, so he may as well enjoy it, he complains about the farce of free will in the eXistenZ game; her retort: "It's like real life; there's just enough to make it interesting."

7. Dead Ringers. 1988. 4 stars. It was only a matter of time before Cronenberg took on gynecology, as what better territory for exploiting the flesh. And what better way to supplement this theme than with the idea of identical-twin doctors (each played by Jeremy Irons), physically separate but joined in mind, sleeping with the same patients who are unaware of being handed off. The beauty of their business, as one of them states, is that they don't have to get out to meet beautiful women, but it's the consequence of this that comes under Cronenberg's microscope. For the twins sex is a passion-less form of surgery -- the point made acutely when one of them clamps his patient down and doesn't release her until orgasm -- and yet, as always with Cronenberg, there is a certain liberating force under that which gratifies on the basest level. Considering this was made in the '80s, it's amazing how convincing the special effects shots are of Jeremy Irons playing the two twins. A creepy tale with pressing questions on genetic identity.

8. A Dangerous Method. 2011. 4 stars. I'd been waiting for a good cinematic treatment of Freud and Jung all my life. For all their quackery, their ideas are part of our Western heritage, and I've frankly never been sure who came off worse. We get to know them from the time they meet in 1907 until their fallout in 1913, and their philosophical disagreements are filtered mostly through Jung's affair with one of his patients. Some complain that Kiera Knightly's performance as Jung's patient/mistress is overwrought, but her jaw-jutting demonic facial contortions are based on historical fact, and I actually thought she did quite well. (And who could fail to be aroused by the floggings Jung gives her?) There are powerful moments between Freud and Jung, the master insisting on sexual explanations to everything, the student veering off, even more questionably, into esoteric mysticism. If The Brood was a body-horror slam on mental therapy, A Dangerous Method is its professional and historically dramatic analog.

9. Shivers and Rabid. 1975, 1977. 3 ½ stars each. These twins have low-budget baggage, but I suppose that's part of their charm like any cult classic. Shivers is perhaps the strongest example of sociological horror I know of. The theme of lonely, conformist, and consumerist people being raped to death by slugs, to rise again as part of a new parasitic world order, has been described by the director, for all its horror, as a liberation. Indeed, one can't help but cheer for the sex-crazed zombies and downfall of society on one level. Many things about this film herald the director's legacy: unnerving clinical atmospheres (the scientist cutting open the school girl and then slitting his own throat is a fantastic opening), unique spins on traditional ideas (zombies who want to fuck your flesh rather than eat it)... a forceful debut for Cronenberg. [It's also known as They Came From Within.]Rabid is the companion follow-up to Shivers, another piece of low-budget cheese that stands on the strength of transgressive creativity. Sex and parasites are again in view, and in another apocalyptic context of global craziness, prefaced (of course) by a cold clinical atmosphere. Marilyn Chambers is somewhat wasted as an alluring vampire who doesn't get to show off much acting, but what her physique has to offer more than compensates. That Cronenberg would come up with a twisted variation on the vampire is a given, but a worm out of the armpit? What part of his demented mind dreamed that up? Rabid deserves a place among the best vampire films of all time, not only for its batshit weirdness, but for waving a prophetic torch to modern science and world issues. This young woman, forced to drink human blood for survival against her will, is as tragic as any Renaissance character out of Anne Rice's tales of the Vampire Lestat.

10. A History of Violence. 2004. 3 ½ stars. It's worth spelling out what Cronenberg was trying to do here, since I think this film is a bit overrated for all the love fans heap on it. The title has three levels of meaning, from the lead character's personal history of violence, to history of violence as a means to an end, to finally the Darwinian implications of the violence in humanity. It adds up to a nice philosophical film-noir thriller, except that Viggo's character, for all his background of bad-assery, is a little too super to take seriously, especially by the end act. This is easily Cronenberg's most commercial film, and based on a graphic novel -- unfortunately feeling too much like that for all its attempts to wrestle with a serious issue. But it is a fun film to watch, no doubt about it. Mortenson and Harris play off each other wonderfully, and scenes of brutal violence and raw burning sex in a small town setting are inherently dramatic.

1. Videodrome. 1983. 5 stars. If there was ever a film that merits the cliche "like nothing you've seen before", this is it. The idea that watching videos can somehow physically change and corrupt you is quintessential Cronenberg, and involves everything from torture porn to sadomasochism to mind control, all weaved through the body horrors of flesh guns, male "vagina" slots that play VHS tapes, and cruel metamorphosis. James Woods fits perfectly in this stew as the CEO of a cable station who gets involved with conspiracies behind a snuff-film franchise, and becomes a pawn in a plot to broadcast its signal to millions of viewers. The mission is to create a "new flesh" by merging human consciousness with a media stream of sexualized violence, and the hyper-commentary is obvious: we're becoming dangerously complacent the more we evolve into a mass-media culture. By far Cronenberg's most original, intelligent, and disturbing film; and his ultimate masterpiece.

2. Crash. 1996. 5 stars. Cronenberg's most fucked up film -- and I mean that in a good way -- is a bit like Pink Floyd's The Wall: just watching it is a drug trip. It explores esoteric fetishism, in this case people who are sexually aroused by car crashes, even fatal ones, and study and ritually reenact the car accidents of celebrities. I would probably call Crash the most artistic NC-17 film I've ever seen. For all the racy material, it doesn't come across as sensational, in fact, just the opposite: it's incredibly subdued and polished. The cold blue look works wonders in this regard, and dialogue seems to be spoken through a dream-like filter. The parallel of surrendering to an automobile wreck and giving oneself up to a sex partner sounds too crazy to take seriously, but it works in context, and indeed this is one of Cronenberg's most serious films. According to him, Crash would have been a cheap Basic Instinct type of thriller in the hands of Hollywood; in his it approaches the artistic nihilism of Ingmar Bergman.

3. The Brood. 1979. 4 ½ stars. This angry film testifies to the nasty divorce Cronenberg was going through at the time, and also to the crank psychoanalytic movement of the '70s. Here the therapy is "psychoplasmics", which attempts to heal mental derangement by a gross physical change to the patient's body; the patient in question is a woman who was abused as a child, and is now in legal battle for custody of her five-year old daughter. In rage she gives birth to deformed children who go on killing rampages, and they even go after her daughter. What keeps this a stand out film is the level of child endangerment we rarely see anymore. The Brood is in some ways an indictment of irrational feminine power, and also contends with the other '79 body-horror classic Alien: the scene with Samantha ripping open her external sac and licking clean her mutant newborn is almost as horrifying as Kane's chestburster. I revere this film, it has high rewatch value, and I wonder if it would have been as effective if not for the personal rage Cronenberg was able to pour into it.

4. The Fly. 1986. 4 ½ stars. A doomed romance is as much responsible for this one's popularity as the hideous horror show. It's astonishing, actually, how much emotion The Fly packs, given the minimal development of Brundle and Veronica's love affair. As for the repulsion on display, it's shocking even for Cronenberg -- animals torn inside out, food being puked on for edible purposes, a woman's nightmare of giving birth to a huge obscene larva. So many scenes have taken on classic status, not least the tragic dialogue at the end, "I'm an insect who dreamed he was a man; but now the dream is over, and the insect is awake," followed by Veronica's anguish as she can barely bring herself to kill Brundle in an act of mercy. If there's any criticism I have, it's the omission of exceptionally gross scenes that were censored in order to keep our sympathy for the protagonist, which was completely unnecessary. Then there's the tacky '80s feel. But it's only little things that keep The Fly from a perfect 5-rating.

5. Eastern Promises. 2007. 4 ½ stars. When Cronenberg left the body-horror genre, reactions were mixed, but this film vindicates the move if nothing else. Viggo Mortenson reprises his shady figure from A History of Violence, but with far more realism and depth -- the fight scene in the bathhouse where he gets the shit kicked out of him is classic, and contrasts in every way with his superhero vanquishing of the thugs at the end of History. Indeed, Eastern Promises exudes a black discipline in every frame; it's Cronenberg's Godfather, no less, with London Russians instead of American Italians, but the same mafia codes of honor and shame, weaved around a business of sex trafficking and a mysterious baby whose mother was murdered. There is the striking absence of guns in favor of knives, which throws a more intimate spotlight on the question of brutal violence. It's as if Cronenberg wanted to show what he could really do this time with Viggo Mortenson as a paradox of corruption and justice, and the result is one of his most artistic films.

6. eXistenZ. 1999. 4 stars. Or The Matrix goes organic. Some believe this film perfected what Videodrome tried in the '80s, but they're in the minority, and I'm certainly not with them. It may be a cleaner and more logical look at virtual reality but doesn't come close to topping Videodrome's raw demented power, let alone innovation. That being said, I really like eXistenZ. It exploits multiple layers of stories within stories, with people assuming different but roles on each level (shades of the later Inception), so even by the end you can't be sure of what's really going on. There's also some fun philosophy about free will. The most notorious scene has Jude Law greedily devouring a disgusting "Chinese special" at a restaurant (it has to be seen to fully appreciate the greenish-black mess of amphibian pus and slime), while also grimacing like he wants to throw up. When his partner tells him he won't be able to stop himself, so he may as well enjoy it, he complains about the farce of free will in the eXistenZ game; her retort: "It's like real life; there's just enough to make it interesting."

7. Dead Ringers. 1988. 4 stars. It was only a matter of time before Cronenberg took on gynecology, as what better territory for exploiting the flesh. And what better way to supplement this theme than with the idea of identical-twin doctors (each played by Jeremy Irons), physically separate but joined in mind, sleeping with the same patients who are unaware of being handed off. The beauty of their business, as one of them states, is that they don't have to get out to meet beautiful women, but it's the consequence of this that comes under Cronenberg's microscope. For the twins sex is a passion-less form of surgery -- the point made acutely when one of them clamps his patient down and doesn't release her until orgasm -- and yet, as always with Cronenberg, there is a certain liberating force under that which gratifies on the basest level. Considering this was made in the '80s, it's amazing how convincing the special effects shots are of Jeremy Irons playing the two twins. A creepy tale with pressing questions on genetic identity.

8. A Dangerous Method. 2011. 4 stars. I'd been waiting for a good cinematic treatment of Freud and Jung all my life. For all their quackery, their ideas are part of our Western heritage, and I've frankly never been sure who came off worse. We get to know them from the time they meet in 1907 until their fallout in 1913, and their philosophical disagreements are filtered mostly through Jung's affair with one of his patients. Some complain that Kiera Knightly's performance as Jung's patient/mistress is overwrought, but her jaw-jutting demonic facial contortions are based on historical fact, and I actually thought she did quite well. (And who could fail to be aroused by the floggings Jung gives her?) There are powerful moments between Freud and Jung, the master insisting on sexual explanations to everything, the student veering off, even more questionably, into esoteric mysticism. If The Brood was a body-horror slam on mental therapy, A Dangerous Method is its professional and historically dramatic analog.

9. Shivers and Rabid. 1975, 1977. 3 ½ stars each. These twins have low-budget baggage, but I suppose that's part of their charm like any cult classic. Shivers is perhaps the strongest example of sociological horror I know of. The theme of lonely, conformist, and consumerist people being raped to death by slugs, to rise again as part of a new parasitic world order, has been described by the director, for all its horror, as a liberation. Indeed, one can't help but cheer for the sex-crazed zombies and downfall of society on one level. Many things about this film herald the director's legacy: unnerving clinical atmospheres (the scientist cutting open the school girl and then slitting his own throat is a fantastic opening), unique spins on traditional ideas (zombies who want to fuck your flesh rather than eat it)... a forceful debut for Cronenberg. [It's also known as They Came From Within.]Rabid is the companion follow-up to Shivers, another piece of low-budget cheese that stands on the strength of transgressive creativity. Sex and parasites are again in view, and in another apocalyptic context of global craziness, prefaced (of course) by a cold clinical atmosphere. Marilyn Chambers is somewhat wasted as an alluring vampire who doesn't get to show off much acting, but what her physique has to offer more than compensates. That Cronenberg would come up with a twisted variation on the vampire is a given, but a worm out of the armpit? What part of his demented mind dreamed that up? Rabid deserves a place among the best vampire films of all time, not only for its batshit weirdness, but for waving a prophetic torch to modern science and world issues. This young woman, forced to drink human blood for survival against her will, is as tragic as any Renaissance character out of Anne Rice's tales of the Vampire Lestat.

10. A History of Violence. 2004. 3 ½ stars. It's worth spelling out what Cronenberg was trying to do here, since I think this film is a bit overrated for all the love fans heap on it. The title has three levels of meaning, from the lead character's personal history of violence, to history of violence as a means to an end, to finally the Darwinian implications of the violence in humanity. It adds up to a nice philosophical film-noir thriller, except that Viggo's character, for all his background of bad-assery, is a little too super to take seriously, especially by the end act. This is easily Cronenberg's most commercial film, and based on a graphic novel -- unfortunately feeling too much like that for all its attempts to wrestle with a serious issue. But it is a fun film to watch, no doubt about it. Mortenson and Harris play off each other wonderfully, and scenes of brutal violence and raw burning sex in a small town setting are inherently dramatic.